The geologic wonders of the Llano Estacado, such as slot canyons, arches, and waterfalls, are all mystic enough. Yet, it is quite possible that the most mysterious features of the Panhandle’s natural history are it’s lithic ones. Rock art sites are probably the most overlooked and forgotten. Of such, probably none are as forgotten as this one.

Most modern Texas Panhandles residents have no clue that such sites even exist on the Texas Plains. Those that do know about them are frequently their most staunch protectors, usually being private land owners who literally shelter them with secrecy and locked gates. The extreme climate of the Llano Estacado with its dramatic fluctuations of wet and dry make fragile rock art vulnerable to erosion and destruction from landslides and other forces of nature. Many more fall victim to vandalism. Not all rock art in the Llano canyons is pre-historic. Many sites found today are likely frontier cowboy art.

Not far off of the well beaten path that once bore the tracks of the Sad Monkey Railroad sits a rock art site that was likely seen by thousands of tourists as a point of interest highlighted by eager-to-impress rail guides. For many, the rock art site likely was a conveniently placed embodiment of the canyon’s place in Native American history. Possibly too convenient.

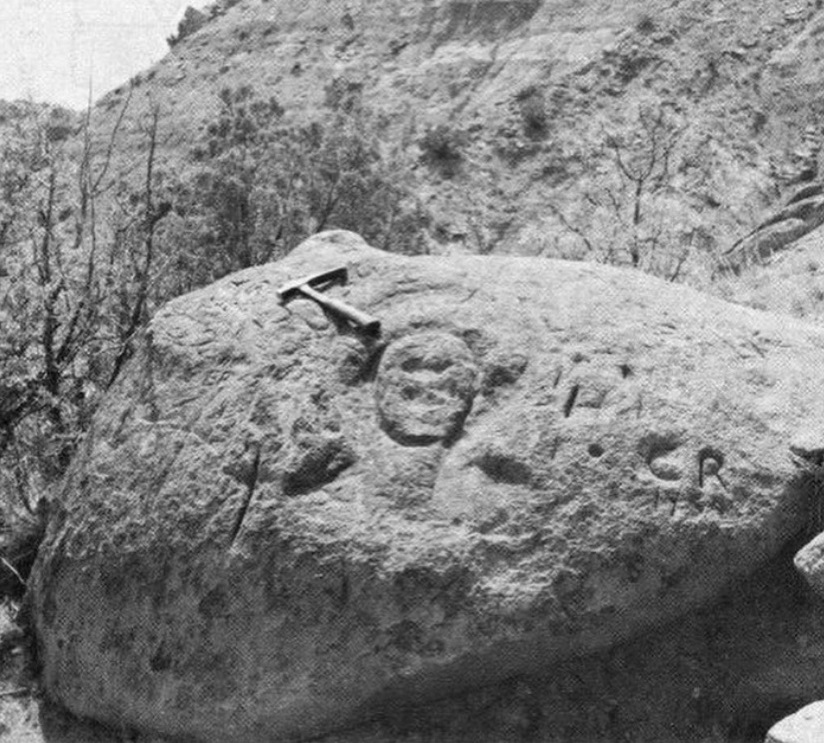

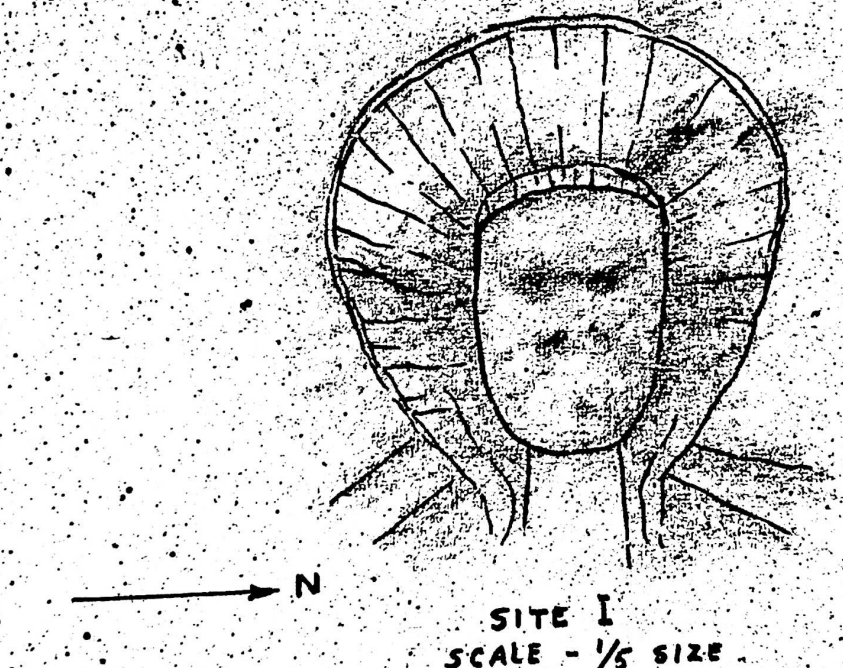

The origin of the Indian Chief glyph is debatable. Its presence in the canyon was of interest to an archeological dissertation at Texas Tech University in the 1970s (Upshaw 1972, figures shown below). The site was surveyed along with a number of other pre-historic sites in the area, but the artist was not determined to be definitively Indian. It could be the work of CCC workers who did extensive projects and make many marks on boulders in the immediate vicinity. As previously inferred, a nicely placed forgery made specially for the eyes of visitors who purchased a ride on the Sad Monkey is also possible.

One thing is certain, the etching has not fared well over the past forty years. In fact, I would name the depicted Indian leader, Chief Crazy Faded! In my mind, this raises questions about the site’s authenticity as a pre-historic Native American site. If it has weathered so much in the last forty years, how could it have survived for centuries? Slide the image bar on the image below to see the visible degradation of the site versus my best effort to carefully and digitally “burn” a highlighted outline of the remnant figure in imaging post processing.

Regardless of the artist’s identity, the Indian Chief petroglyph should prompt us to consider a few important facts about rock art on the Llano Estacado and in its Caprock canyons. While landowners fortunate enough to have these historically important places on their land have a tendency to guard their presence with silence and secrecy, it is vital to recognize that time itself is destructive. Responsible documentation by archeologists and historically-inclined photographers should be allowed before these sites vanish forever. Secondly, while we cherish records in stone left by past generations, modern vandalism and graffiti have no place in natural places. With today’s technology, there is no acceptable reason to leave your physical mark on the natural world, and those that do so should be pursued according to the laws that protect such places.

While ‘Chief Crazy Faded’ (my sarcastic name for this particular site) may or may not be legit, even he who was the subject of exhibit for paid tours and seen by thousands has not just faded from mere physical existence but also in the memory of many who grew up frequenting our great state park. A worse fate of obscurity may await many more historically sensitive sites along the Llano’s edge as their existence is not just forgotten, but never acknowledged, their stories never understood, and their lessons never learned. There is so much history hidden deep within the folds of Triassic sandstones of the Texas Panhandle, some of it is not only hidden, it is purposefully concealed. While preservation has to be the priority, for what reason if not to inform modern and future generations of those that inhabited these canyons before us? Before we transformed the plains above, these canyons were more than pure recreational lands, they were a way of life, and the messages from that way of life should be recorded and heard today.

Thanks for recording what you see on your treks through all sorts of canyons and slot canyons.

The Running Horse site you recorded several years ago on Mott Creek Ranch has likewise suffered from nature’s extremes, 34 inches of rain one year to 5 inches another year, a massive ice storm followed by an Artic blast, and now drought again. It does make us wonder how any of these sites remain.

Thanks for your kind note, Marisue. Merry Christmas to you and your family!